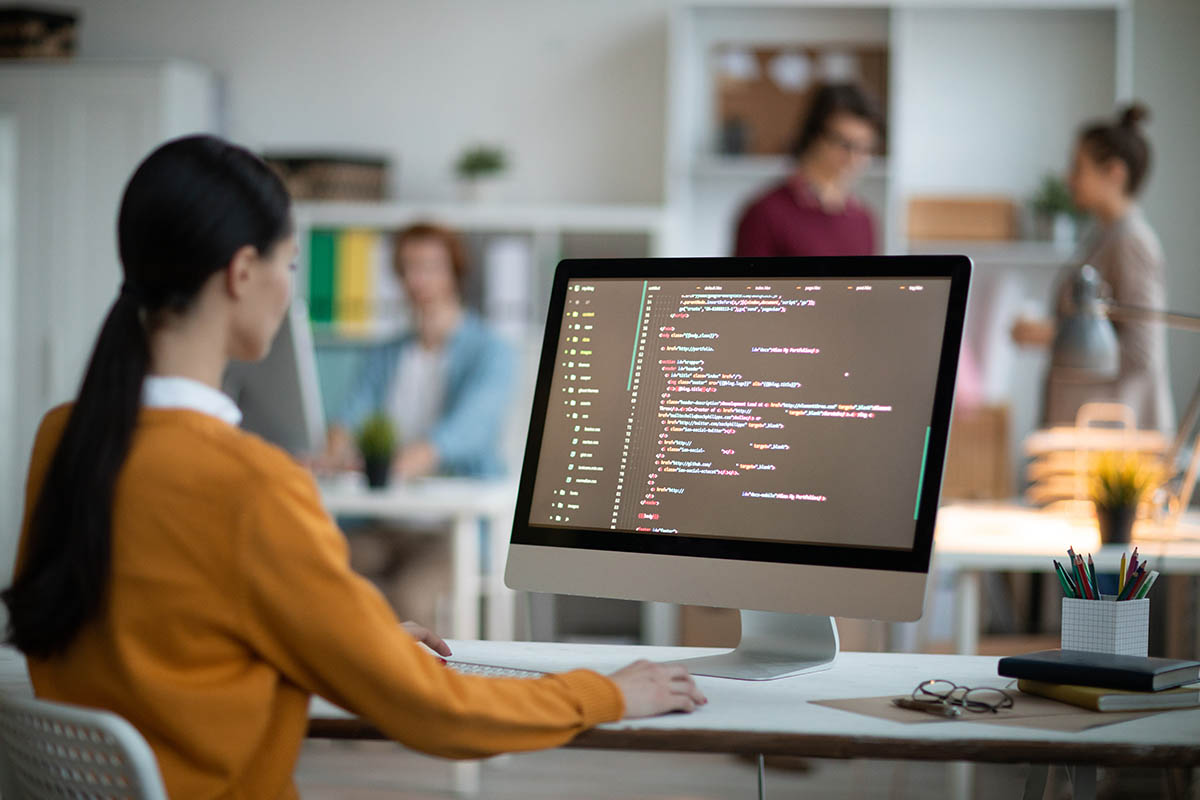

The EU has just released its latest figures about counterfeit products seized at European borders in 2006, and the music industry’s international trade group (IFPI) has jumped on those numbers to call for increased action against Chinese pirates.

Of the 23 million counterfeit CDs and DVDs seized by police last year, 93 percent of them originated in China. The EU is worried enough about the numbers that it is contributing to a US-led WTO case against China over the matter.

But does means one of these discs means that you could be supporting terrorism?

According to the IFPI, it does.

The group yesterday released a list of 10 “inconvenient truths” about music, and it makes for interesting reading. Here they are:

- Pirate Bay, one of the flagships of the anti-copyright movement, makes thousands of euros from advertising on its site, while maintaining its anti-establishment “free music” rhetoric.

- AllOfMP3.com, the well-known Russian web site, has not been licensed by a single IFPI member, has been disowned by right holder groups worldwide and is facing criminal proceedings in Russia.

- Organized criminal gangs and even terrorist groups use the sale of counterfeit CDs to raise revenue and launder money.

- Illegal file-sharers don’t care whether the copyright-infringing work they distribute is from a major or independent label.

- Reduced revenues for record companies mean less money available to take a risk on “underground” artists and more inclination to invest in “bankers” like American Idol stars.

- ISPs often advertise music as a benefit of signing up to their service, but facilitate the illegal swapping on copyright infringing music on a grand scale.

- The anti-copyright movement does not create jobs, exports, tax revenues and economic growth–it largely consists of people pontificating on a commercial world about which they know little.

- Piracy is not caused by poverty. Professor Zhang of Nanjing University found the Chinese citizens who bought pirate products were mainly middle- or higher-income earners.

- Most people know it is wrong to file-share copyright infringing material but won’t stop till the law makes them, according to a recent study by the Australian anti-piracy group MIPI.

- P2P networks are not hotbeds for discovering new music. It is popular music that is illegally file-shared most frequently.

It’s a strange mix of the obvious and the bizarre. Point four, for instance, is probably true, and it won’t come as a surprise to anyone who reads point eight that impoverished Chinese farmers are not the ones doing most of that country’s illegal downloading.

Point three is an odd one; certainly, somewhere in the world, someone with terrorist intentions has made a few bucks from the sale of counterfeit discs. But every other point on the list concerns digital file-swapping, not the purchasing of counterfeit CDs on Parisian street corners. It looks like a subtle attempt to elide the distinctions between the two.

Point five is an attempt to turn the “innovation” argument on its head. For years, pundits outside the music industry have accused labels of pandering to teens through boy bands and “manufactured” celebrities instead of being concerned with finding, producing, and releasing art. The IFPI suggests that the labels could (and would) be doing exactly that if file-swapping went away.

And then there’s point seven, which isn’t an “inconvenient truth” at all but more of a rant against those who prefer giving copyright holders less than absolute control over reproduction rights. An “anti-copyright movement” does exist, but most of the critical voices in the debate recognize the value of copyright—and actually produce copyrighted works themselves (Lawrence Lessig, etc.).

The second part of the accusation (“pontificating on a commercial world about which they know little”) is hardly a statement of fact; it comes across as angry retort to those outside the music business who would dare to criticize its methods and goals.

It’s too bad that groups like the IFPI resort to such dubious statements to make their point. Unauthorized file-swapping of copyrighted works is already illegal in most countries; if people are continuing to engage in it, they are unlikely to be swayed by broadsides against “anti-copyright” crusaders or accusations of funding terrorists.

When it comes to stopping commercial piracy, we applaud the IFPI for its work. When it comes to disparaging those who favor a softer copyright policy, Ars has an inconvenient truth of our own to share with the music industry: these are the sort of tactics that only entrench consumer opposition.